Thursday, September 28, 2006

Better than counting sheep

Not what the doctor ordered

"Frist performed about as well as a heart surgeon with mittens on. He failed utterly to provide the leadership necessary and managed to so mangle the reputation of the legislative wing of the Republican Party in the process that it may take several elections, and perhaps a Hillary Clinton presidency, to recover. . .OK, maybe that is a little tough. But it is especially damning how much trouble Frist had getting things done with 55 votes. The last time the Republicans had more Senators was when they had 56 between 1929 and 1931 (note they also had 55 in the late 1990s, but that was when there was a Democratic president). If you are going to have trouble getting things done with that number of seats and a President and House of the same party, when exactly are you going to get stuff done? And before I hear that I'm not being fair from some proponent of Frist's quixotic presidential ambitions, I realize how tough the job is. He decided to take it on, however, and therefore we are right to analyze his performance. Are we only to expect effective leadership when the majority has 60+ votes? Of course not. Which brings us to how to improve things going forward:

He managed, despite a compliant House, a supportive president, and 55 votes, to pass very little and achieve almost nothing."

"So what is the lesson for the future? A majority leader must not just be from the Senate. He must be of the Senate. He or she need not only sit in the body, but they must ooze its traditions, savor its tempo, grasp its inhibitions, and challenge its institutional lethargy. A good leader needs to grasp that each Senator is really more like a head of a country than a legislator. House members travel in groups. Senators walk alone and above it all. He needs to grasp what their political needs are and figure out how to appease them while, at the same time, leading them."I think this is partly wrong. I'm of the mind that there is actually too much respect for the "traditions" of the Senate, and that what it needs is a little more shaking up. You might not like everything that a Tom Coburn does, for example, but at least he's trying to clear some of the cobwebs from the place. We somehow have slipped into this habit of thinking that things the Senate has done for a long time have some constitutional basis. Instead most of them simply fall under its ability to make its own rules. A party (or movement) confident about its positions and purpose should not be shy about advocating for changing such rules when needed. Remember, their constituency should not be incumbent Republican senators, but rather the people who put them there.

This lack of respect for Senate traditions on my part may raise hackles among conservative readers. Some will quickly remind me to be wary, for example, of curtailing the right to stop legislation (anonymous holds anyone?), lest we need to use such tools ourselves in the minority. I say the way to avoid that problem is to win elections, and the way to do that is to deliver on the campaign promises you make to get elected.

In the meantime, treating senators a bit more like "legislators" wouldn't hurt, either.

UPDATE: For the record, the flurry of legislation that came out of the Senate the past few days doesn't alter my feelings about Frist's leadership. I think a look at the whole tenure still supports what I said above.

Something lighter, part II

UPDATE: The originally linked video was taken down by YouTube, so I've updated the link to a similar copy.

UPDATE 2: The embed seems to have trouble loading sometimes, so here is a direct link.

Tough love

So, to show people that I do more than sift over budget figures and news feds all day, here is a great smack down of Clay Aiken by Simon Cowell. Gadfly is a big fan of tough love, and this may be the first in a series. Just play the video.

Wednesday, September 27, 2006

Oratorical envy

The latest example of Blair's skill was seen yesterday at a Labour Party conference, a clip of which can be found here. Listening to that excerpt reminded me how much I enjoyed his address to Congress a few years ago. I went and found the transcript online, and it lived up to my recollection:

"There is a myth that though we love freedom, others don't; that our attachment to freedom is a product of our culture; that freedom, democracy, human rights, the rule of law are American values, or Western values; that Afghan women were content under the lash of the Taliban; that Saddam was somehow beloved by his people; that Milosevic was Serbia's savior.The part of the speech that I liked the best at the time, though, and again today was the end:

Members of Congress, ours are not Western values, they are the universal values of the human spirit. And anywhere...

Anywhere, anytime ordinary people are given the chance to choose, the choice is the same: freedom, not tyranny; democracy, not dictatorship; the rule of law, not the rule of the secret police.

The spread of freedom is the best security for the free. It is our last line of defense and our first line of attack. And just as the terrorist seeks to divide humanity in hate, so we have to unify it around an idea. And that idea is liberty."

"And I know it's hard on America, and in some small corner of this vast country, out in Nevada or Idaho or these places I've never been to, but always wanted to go...I like that part so much because it correctly captures and then addresses the American reluctance to engagement that characterizes many of us and much of our history. I know my friends from Europe and elsewhere find that tough to believe, but I also think that many of them have spent little time with the great bulk of America that lives outside New York and Washington. America correctly feels burdened, and struggles to understand why others don't see that.

I know out there there's a guy getting on with his life, perfectly happily, minding his own business, saying to you, the political leaders of this country, 'Why me? And why us? And why America?'

And the only answer is, 'Because destiny put you in this place in history, in this moment in time, and the task is yours to do.'

And our job, my nation that watched you grow, that you fought alongside and now fights alongside you, that takes enormous pride in our alliance and great affection in our common bond, our job is to be there with you.

You are not going to be alone. We will be with you in this fight for liberty.

We will be with you in this fight for liberty. And if our spirit is right and our courage firm, the world will be with us." (emphasis added)

And the answer is that such is the hand we were dealt. Life is unfair, its burdens falling unevenly, its calls to leadership going out to certain peoples at certain times. Tony Blair gets it. I hope that the next leader that Britain chooses does so as well.

Excellent, excellent questions

"But the real problem is within the intelligence community. Selective CIA leaks are the equivalent of intelligence officials running information operations on the American public. John Negroponte and Pat Kennedy, how long are you going to allow these leaks to continue? Do you really think it healthy in a democracy for the CIA and DIA to stray from intelligence collection and analysis into politics? How many investigations have you launched? How many have concluded?" (link)

Don't hold your breath for any answers.

UPDATE: Related thoughts well worth your time can be found here.

Tuesday, September 26, 2006

Clinton's poor judgment

So I, similar to others, had hoped that we could put these questions behind us. They serve no useful purpose, and distract us from the important issue of focusing on what we are going to do moving forward. Alas, some are not content to let sleeping dogs lie. The latest chapter is the interview President Clinton did with Chris Wallace over the weekend. Wallace asked why he didn't "connect the dots" and do more to deal with Al Qaeda when he was President.

What Clinton should have done was say that we did what we thought was right at the time, but now in the post-9/11 world we realize that some of our operating assumptions were wrong, and that a different approach is needed. That would have been gracious, and let the issue pass. Instead, he attacked.

The problem with attacking is that it reopens the issue. Now, predictably, people are going to start paying attention to what he actually did and said. Was there really a plan to invade Afghanistan? Did we really need the FBI/CIA to "certify" Bin Laden's guilt? Was there a "comprehensive strategy" in place? What did Richard Clarke actually say in his book? All of this could have been avoided with a "we were all wrong" mea culpa, but that apparently was not to be.

This is a terrible fight to have as a nation, and I'm pretty sure it is a lousy political fight for the Democrats to pick as well. Anyone who thinks that the gathering storm, if you will, wasn't gathering well back in the 1990s (as opposed to somehow emerging with a vengeance in Bush's first eight months in office) is either disingenuous or nuts.

If it is true that the Democrats generally do poorly politically when elections are focused on security concerns, does it really do the party much good with the great middle of American politics to remind them how poorly they did operationally when last they ran things. I think not.

UPDATE: David Frum reviews some of the 9/11 Commission Report, while Captain Ed publishes an update to his earlier post and concludes with this:

"We have now had a week of this debate. Does anyone feel any safer because of it?"Also check out this article by Richard Miniter.

Wal-Mart and drugs, revisited

"Rick Hans, Walgreen's director of finance, said during the call that he believed Wal-Mart's low-price plan for some generic drugs 'won't significantly impact [Walgreen's] business.'This nicely - although unintentionally - demonstrates a key part of what is wrong with the way we pay for a lot of our health care. Hans is comparing the total cost that Wal-Mart is charging with the portion of Walgreen's price that consumers have to pay (i.e. the co-pay). What he is obviously ignoring is the additional amount, above the co-pay, that the insurance company or the government is paying to Walgreen as well.

The Wal-Mart plan covers 291 drugs, while Walgreen pharmacies stock about 1,800 generic drugs, he said.

'About 95 percent of our pharmacy patients have prescription insurance coverage and they are only responsible for a small co-pay,' Hans said.

He added that for the drugs that Wal-Mart will sell for $4, the initial average co-pay at Walgreen is $5.30, and $3.18 for Medicare Part D prescription coverage."

Separate those who make the decision from those who pay for the decision, and you shouldn't be surprised that costs tend to rise. The interesting thing to watch here will be if insurance companies start to either require or encourage (perhaps through the waiving of co-pays?) their members to use Wal-Mart where the program is available. Given that type of development, will Walgreen then drop its prices as well? It certainly hopes not:

"'Our convenience, locations and services have proven to be bigger factors for our patients than a few dollars in price difference,' he said."That is a reasonable and - in my mind - rather optimistic hypothesis. It is also one that seems about to be tested.

Monday, September 25, 2006

The long haul

"I remind Rumsfeld that, when we last talked — three years ago — I asked him whether the American people would stick with the War on Terror. And he replied, on that occasion, 'They stuck with the Cold War.'We have a tendency to romanticize things that have come before - to think that people were more united than they were, that the eventually successful strategy was obvious to all (or any) at the time, that there weren't people thought to be right in the moment who were proven to be wrong in the end. It is useful to remember that history is always messy, especially when it is being made.

'Yeah,' Rumsfeld says now. 'Long time. Lot of wavering. A lot of cold feet at the various points along the way. I remember being in Spain and getting a phone call saying I had to come back to testify against the Mansfield Amendment,' which proposed to pull U.S. troops out of Europe. 'I was ambassador to NATO at the time — early ’70s. And here you are: The Cold War’s in full flower, and the Soviet Union’s making mischief in Central America and Africa and subjugating Eastern Europe . . .' Yet the proposal was made all the same. . .

So, continues the SecDef, 'you look back on it now and say, ‘Oh, my goodness, it was a good, straight, upward path. We all knew all along the Cold War would last a long time. We knew all along it would be tough, but we never wavered and never doubted.’ And we did waver and doubt, and there were plenty of people who got cold feet as they went along.' . . .

The Terror War, says Rumsfeld, is 'going to be long, much more like the Cold War than World War I or II in terms of length.' And it’s going to be won, 'as much as by anything,' by 'people within that faith,' Islam, 'who don’t want to see their religion hijacked and who are not violent extremists and who do not get up in the morning and think that beheading people and forcing everyone else to be exactly like they want them to be is the preferred way of life.'"

Oh and by the way, I'm pretty sure Rumsfeld wasn't talking about this guy when he was discussing who needs to step up within Islam:

"Sheikh Abu Saqer, leader of Gaza's Jihadia Salafiya Islamic outreach movement, which seeks to make secular Muslims more religious, called for holy war against the Pope.

He said Christian leaders such as Benedict XVI are 'afraid' because they realize Islam is Allah's favorite religion and that they are going to hell unless they convert. The Gaza preacher declared the 'green flag of Muhammad' would soon be raised over the Vatican. . .

Abu Saqer claimed he did not condone violence. He blamed the pope for recent anti-Christian attacks in the Palestinian territories.

'We are deeply sorry for these acts that we condemn. But I am sorry that this little racist did not think of the consequences upon the Christians in the Arab world when he insulted our Prophet. It is an open war - the Muslims against all the others.'"

Be careful of opening that door

"'Those who habitually accuse us of 'not doing enough' in the war on terror should simply ask the CIA how much prize money it has paid to the government of Pakistan,' he [Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf] says, without specifying where the money came from." (link; via Drudge)

Or maybe we should ask what type of ally would have us pay it "prize money," or what those nearly 700 Al-Qaeda suspects were doing in Pakistan to begin with, or how this "truce" is going to work. I'm just saying . . .

UPDATE: File this under unbelievable (hat tip: Alarming News):

"'Pakistan's military ruler, Pervez Musharraf, says he contemplated war with the United States in 2001 but opted instead to forsake the Taliban and become President George W. Bush's ally,' the Globe and Mail reports."

The article goes on to describe how Pakistan "war-gamed" conflict with the US and, after discovering it would lose, then decided to support US efforts. It follows, then, that if they thought they could resist US military pressure, they would have fought on the side of the Taliban?

Nice to know who our friends are.

Oh, and not for nothing, but maybe all that unified, global sympathy that I keep hearing we squandered after 9/11 didn't run quite as deep as some would have you believe, if in the aftermath Pakistan was trying to figure out if it should take us on in battle.

Whither the newspaper?

"It seems hopeless. How can the newspaper industry survive the Internet? On the one hand, newspapers are expected to supply their content free on the Web. On the other hand, their most profitable advertising--classifieds--is being lost to sites like Craigslist. And display advertising is close behind. Meanwhile, there is the blog terror: people are getting their understanding of the world from random lunatics riffing in their underwear, rather than professional journalists with standards and passports."For the record, I rarely riff in my underwear. What I want to concentrate on, though, is the economic situation newspapers find themselves in.

To me, the interesting thing here is that through historical accident and the nature of print distribution, the classified business and the news business became tied. There is no reason that they have to be, and - more to the point - no reason to think they ever will be again. The part of the newspaper that Kinsley wants to keep (the original reporting) has never paid for itself. It has always been supported by the fairly profitable business of classified advertising. This accidental relationship has allowed professionals in the business to delude themselves regarding what people were actually paying for.

Here's the truth that hurts: people don't apparently value the journalism that many papers produce as much as the journalists think that they should. This fact was able to be obscured for quite a while by the fact that people did value something else the newspaper provided (classified advertising) quite a bit, and tolerated the cross subsidization as a result. That subsidy relationship has now been broken, and how much most people are actually willing to pay for the news is becoming clear - not that much. That smarts if you are a reporter or editor, but then again I'm sure it also smarts if you work at GM and watch people not want to spend money on your product either. Complaining about the fact that it hurts, though, is not a strategy for future success.

Options? Assuming that the classified business is for all intents and purposes lost, one option would be to try to tie news reporting to something else that people value. Nothing likely to work comes to mind. They might also become trophy properties (as Kinsley alludes to), where rich people buy them for the ego boost and then proceed to subsidize them from their existing wealth (similar to many sports teams). Alternatively, they will have to "right-size" themselves to a level that can be supported by the people who want to read them.

On this last point, though, I am curious about what a completely "e-paper" might look like. There certainly is a market for "serious" news; the problem is that that market is a lot smaller than traditional newspapers have let themselves believe. The good news, though, is that those "serious news" consumers are a lot more technologically literate than the average population, and probably have higher average incomes as well (making them a potentially attractive online advertising demographic). Move completely online, and your eliminated costs include paper, printing plants, and a lot of the layout work. Would that be enough to support a smaller operation, but one more focused on the actual news? I don't know, but I do know that there are a lot of people around the country right now that better start thinking about it.

By the way, if you are interested in another take on Kinsley check out Ace of Spades, who has thoughts more from the journalistic aspects of the issue.

Saturday, September 23, 2006

Amaranth - that didn't take long

"Randall Dodd, president of the Washington-based Financial Policy Forum, said Amaranth's collapse highlights cracks in the nation's capital structure and, because of the unregulated nature of both energy derivatives and hedge funds, policymakers have no idea how deep those cracks are.How exactly has this affair highlighted any "cracks" in the nation's financial system? A specific fund made a (stupidly large, for the fund's size) bet that the spread between March and April 2007 gas futures would behave a certain way. They were wrong, and they rightly lost a lot of money. (I should note that, given the nature of derivatives contracts, the money they lost was actually made by others, but that is a subject for a different post.)

'We don't know how many more Amaranths are out there,' Dodd said. 'Several falling is a problem for the whole financial system.'"

The most important part to realize is how well the overall system worked here. Notice that the positions which caused the problem were contracts that are due in March and April of next year. As those positions moved against Amaranth, banks and counter parties presumably required increased collateral to make up for the paper losses (as opposed to waiting to see if the firm could pay up next year). By requiring increased funds now to keep the positions open (basically, a margin call), these market participants forced the issue when Amaranth still had enough capital to get out of their commitments (albeit at steep losses to the firm). The nightmare for the rest of us isn't that Amaranth lost a ton of their money; the nightmare would be if when those futures contracts expired the firm couldn't make good on their commitments. And that is a scenario that seems to have been nicely avoided.

But don't worry, the politicians are on it:

"The political fallout from Amaranth's troubles had reached Capitol Hill by the afternoon of Sept. 19. Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), who has a bill before the Senate to require OTC energy traders to report their positions daily, reiterated her call for more regulation.'This is a graphic and very expensive example of the need for legislation that would increase transparency and accountability in the energy markets so the federal government could determine if speculation or manipulation is occurring,' Feinstein told Platts.""Speculation" is now illegal? Please.

Listen, it sucks right now to be an investor in Amaranth. It may even turn out that they have a cause of action, if - as I suggested earlier - the firm violated the terms of their agreements. If Amaranth didn't violate the terms of their agreements, however, then it will suck even more to be an investor in Amaranth. Because in that case they will only have themselves to blame.

Gadfly takes requests, part II - Wal-Mart and drug prices

"Even company critics have praised the plan, conceding that it represents a case of the giant retailer using its size and ability to wring out costs to improve the lives of regular Americans. . .The generic drug market is already incredibly competitive at the manufacturing level; it's great to see Wal-Mart bring some old fashioned market pressures to bear at the distribution end of the market. Hmm, how long will it be before we hear calls of "unfair competition," since smaller pharmacies likely wouldn't be able to benefit from (and then pass along) similar economies of scale? Maybe the company's critics will skip this one. . .

As it has for dozens of consumer products, Wal-Mart reduced prices of generic prescription drugs by attacking the few remaining pockets of inefficiency in its operations. For example, it cut out third-party distributors that stood between the chain and drug manufacturers. . .

The company also introduced rapid, automated machines into its pharmacy distribution centers that had long relied on workers to fill orders. In doing so, Wal-Mart reduced the amount of time that costly drugs sat in warehouses, rather than on store shelves where they could create revenue. 'It is not glamorous,' said Bill Simon, an executive vice president at Wal-Mart. 'It’s pennies at a time.'"

Let me take the opportunity, by the way, to draw a distinction between these generic medicines and newer ones that are still under patent protection. Basically, we have to be willing to stomach high drug prices for the first 10 years or so that treatments are on the market. That's the price we as a society pay for the remarkable amount of money that is spent on medical research and development each year. These investments have no guarantee of return, and very often wind up amounting to no benefit for the companies involved. Limit the ability to earn economic rents during patent protection periods, and the level of resources devoted to new treatment development will drop.

As for those drugs whose patents have expired, however, let competition drive down the prices as far as possible.

Gadfly takes requests, part I - HIV testing changes

The government has recommended HIV tests as part of routine medical care, a change from their historical position. Bravo. We're 25 years into this thing, AIDS is a disease with existing but imperfect treatment options, and it is time we regularly treated it as such.

Not everyone agrees, however:

"Rose A. Saxe, a staff lawyer with the AIDS Project of the American Civil Liberties Union, said her group opposed the recommendation because it would remove the requirement for signed consent forms and pretest counseling. In settings like emergency rooms where doctors are strapped for time, Ms. Saxe said, 'we’re concerned that what the C.D.C. calls routine testing will become mandatory testing.'I think this type of testing should follow the model of blood work, which gets screened for lots of things (doctors in the audience, help me out with other examples of things blood is normally tested for). If I ran the world, someone who consents to blood work consents to the rest of the medical tests that would normally go with it (unless they specifically ask to opt out, I guess) What could a rational, intelligent, defensible position be for not knowing one's HIV status, especially in 2006? I don't sign a special consent to find out my cholesterol levels, and I see no need to do so for an AIDS test.

Patients, particularly teenagers, she said, 'will be tested without an opportunity for understanding the magnitude of having a positive result.'"

As for the idea of the need for deep, pretest counseling? Nonsense. What other diseases do we require this type of approach for? I go in for a check-up, and might wind up having a prostate exam. The doctor doesn't spend time with me beforehand to explain that - even if he feels something and even if it eventually turns out to be prostate cancer - in general prostate cancer grows very slowly, and if we catch it early there are a variety of courses of treatment available, etc. No, that is not done; instead we cross that bridge when we come to it. Of course it would be terrific if we all had lots of pretest counseling, became perfectly-informed patients, etc. But to stipulate it as a requirement, and by extension prevent testing when it does not occur, is in my mind wrong.

Once again, AIDS is a disease. We all benefit - those who are or will be sick most of all - from people knowing when they are infected/sick with a disease. Attempts to continue to treat AIDS as in a "special" category are wrong-headed, and a long time past their prime.

Thursday, September 21, 2006

Disaster at Amaranth

"'What type of regulation would prevent a hedge fund from following a particular investment strategy, or the loss incurred in the pursuit of an investment strategy that simply did not work,' said Perrie Weiner, a partner who helps manage law firm DLA Piper Rudnick Gray Cary's securities litigation practice and often deals with hedge funds."The answer is none. There are two important issues in this specific situation:

- One, did the firm in fact do what it told its investors it was going to do, most importantly in its offering documents, but also in other communications? A simple example would be a firm that said it was going to buy common stocks, and instead speculated in energy futures (not the case here, but you get the idea).

- Two, should investors demand more specificity in such documents about what firms are allowed to do in a particular fund? The most striking thing about the Amaranth situation is that they allowed the firm to be so incredibly exposed to a move against them in a single market (i.e. natural gas). Investors might, quite rightly, begin demanding more specific, quantitative risk control guidelines be included in offering documents. These might include limiting individual (or related) positions to a certain percentage of fund capital, formalized stop-loss guidelines, etc.

Come to think of it, there actually is another big issue, and the fact that it hasn't really come up shows you that the system works. Was there any chance of a broader market breakdown or disruption because of this individual failure? You may recall that it was just this type of fear (whether or not it was justified) that caused the NY Fed to help orchestrate a private bailout of Long Term Capital Management back in 1998. In this case, despite what would appear to be a very concentrated portfolio exposure to natural gas, I haven't seen worries about derivative contracts not being honored, or other systemic concerns. In fact, it seems that non-energy parts of the portfolio were being liquidated in order to meet the collateral requirements of the gas positions. If that's the case, then the banks and others involved did the job they were supposed to do, and limited the damage to Amaranth.

Remember, when dealing with sophisticated funds and investors, regulators aren't around to stop them from losing money by making bad bets. Instead, they are around to stop those bad bets from hurting others. It seems in this case that system worked fine.

Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus

"Sorry, you're confusing me with the other Senator from Massachusetts"

Photo is by Rodney White, The Des Moines Register. Here is a link to the story.

Sorry, I just couldn't resist. Any better caption ideas? Leave them in the comments.

The media must hate the internet

- Here the AP is caught changing titles pretty significantly in an article about some poll numbers. Ah, wishful thinking.

- Here is a different sort of problem, with CNN tailoring headlines by geography.

Listen, these two aren't the biggest deals in the world, and we'll spend time (maybe lots of time) in the future on what I think are much more serious examples of media bias, etc. That said, you just know that the new level of accountability that the internet and other resources demand drives the traditional media outlets nuts.

Wednesday, September 20, 2006

Best line by a smart person I've read all day

"In conclusion, if you think that the things the Bush administration is doing could, in the future, help less benign governments to seize horrifying power--well, I'll agree with you, but only if you also acknowledge that the same could be said for every president since Hoover, and that in fact FDR takes the gold prize for Doing Things That Could Be Used to Install a Dictator. Indeed, FDR is probably the closest thing this country ever came to having a dictator, and we can thank a lot of fast tap-dancing by the Supreme Court and the Senate for not getting us closer still. If FDR doesn't terrify you, then you will have a very stiff uphill battle explaining to me why Bush does." (emphasis added; link)If you don't regularly read Asymmetrical Information, you should. Some great, accessible economics blogging.

As an aside, I also think Megan says some interesting things about torture in the post, some of which are similar to thoughts I've had. I'm planning on doing a longer post about them at some point, especially given all the attention Andrew Sullivan has been paying to the subject.

Man, that Karl Rove is smart

"When are we going to hear that the Pope's comments were intended to help the GOP in the midterms? It just seems so obvious. White ethnic Catholics are reminded of the war on terror when they hear people calling for suicide attacks on the Vatican. That can only help the GOP. Where is Gore Vidal to fill in the details?"I was in the process of writing a quick post - and laughing out loud - about this joking note by Jonah Goldberg, when I then saw he posted an update. Apparently, to some this is no joke - look here and here.

Come on folks, why stop there? What makes you think all those pictures of protesters are real? As 9/11 conspiracy theorist Morgan Reynolds says, in discussing the fact that he doesn't think any planes hit the World Trade Center:

"But what about all those New Yorkers who saw airplanes hitting the twin towers? A chuckle rumbles down the phone line. 'I don't believe anyone in Lower Manhattan,' [Reynolds] says. 'You hire three dozen Actors' Equity dudes and they'll say anything.'"

So maybe a lot of previously unemployed actors have recently been sent on a road gig?

Doesn't it just amaze you how nuts some people are?

Keep your hands off my secrets

First of all, some background on what we are talking about here for people not familiar with the business. Firms that hold more than $100m in stocks have to disclose their positions in a quarterly filing. This filing is only a snap shot (like a partial balance sheet), and there is a lot that it will not tell you about the fund. You'll never know about any trading within a quarter, only the net effect at the end. It doesn't disclose short positions, nor any information about options (either long or short). Finally, there is no information about the amount of leverage used (or cash held in reserve).

So, how strong is the case? Well, all the details of a firm's investment activity taken together are certainly a trade secret, and potentially incredibly valuable. These details are the transcript and blueprint of the "product" produced by money managers, namely a series of time-sensitive buy and sell decisions involving a number of different securities (and potentially asset classes). Investors (especially in hedge funds) pay enormous sums to acquire this product; to be forced to disclose all would be to de facto steal from the managers, and also have the investors in the fund subsidize those in the public who would use the disclosures to their own benefit.

So, if disclosing all the investment program details would be so bad, what about the partial disclosure required in a 13F? They are partially bad, and the amount of useful information disclosed varies greatly depending upon the type of fund involved. The most affected are long-term, long-only shops - a careful following of their 13Fs would allow you to almost completely mimic their investment program for free (albeit with a significant lag).

It would seem that, absent some compelling public interest, disclosure should not be required. What, then, is the interest?

Remember that certain other types of disclosure would not be affected if 13Fs were done away with. For example, buying more than 5% of a company's stock would still trigger a reporting requirement. Also, investors in a fund itself could demand certain disclosures, and - if they were not satisfied - refuse to invest and take their money elsewhere. And access to investor lists for things like proxy fights would likewise be unaffected.

In the end, it seems the current disclosures do little other than to feed a need for voyeurism (of which I have been guilty) among professional investors and to satisfy the inertial wants of the regulatory bureaucracy at the SEC. Neither of these reasons strike me as compelling, certainly not enough to appropriate part of the investment program that others are paying so dearly for.

I agree with Goldstein. Am I missing something?

Bush at the UN

"Some have argued that the democratic changes we're seeing in the Middle East are destabilizing the region. This argument rests on a false assumption: that the Middle East was stable to begin with. The reality is that the stability we thought we saw in the Middle East was a mirage.The second one was a nice little dig at his hosts:

For decades, millions of men and women in the region had been trapped in oppression and hopelessness. And these conditions left a generation disillusioned and made this region a breeding ground for extremism.

Imagine what it's like to be a young person living in a country that is not moving toward reform. You're 21 years old, and while your peers in other parts of the world are casting their ballots for the first time, you are powerless to change the course of your government. While your peers in other parts of the world have received educations that prepare them for the opportunities of a global economy, you have been fed propaganda and conspiracy theories that blame others for your country's shortcomings. And everywhere you turn, you hear extremists who tell you that you can escape your misery and regain your dignity through violence and terror and martyrdom.

For many across the broader Middle East this is the dismal choice presented every day. Every civilized nation, including those in the Muslim world, must support those in the region who are offering a more hopeful alternative."

"To the people of Darfur, you have suffered unspeakable violence. And my nation has called these atrocities what they are: genocide."If you are unaware, the comment was a reference to this. Take a look - doesn't it almost seem like a spoof of what you thought a competent authority would do, more concerned with scoring law review rhetorical points than stopping the homicide in question? It makes me more and more inclined to agree with this type of thinking (which is quite good, and worth your time to check out).

Tuesday, September 19, 2006

Depressing, but predictable

This is what you get.

Drug development is incredibly long, costly, and unpredictable. Even worse, there are rarely clear cut home runs. Almost any treatment has side effects of some sort, the question is always whether or not the benefits outweigh the costs. There are reasons that biotech and pharmaceutical companies get it wrong so often, and that billions and billions of investor dollars are spent each year on programs that eventually wind up failing (many miserably). In short, this stuff is really, really hard to do, even for the smartest people out there.

This is not a "point the fingers" post. This is a "this is scary for all of us" post, perhaps even more so for those of us who live in Manhattan or other likely targets. And a large part of the scariness is how little can really be done about it.

Depressing, but predictable. Or maybe predictably depressing.

Show them the respect of believing what they say

"A cult of death is forming in the Muslim world — for reasons that are perfectly explicable in terms of the Islamic doctrines of martyrdom and jihad. The truth is that we are not fighting a 'war on terror.' We are fighting a pestilential theology and a longing for paradise.

This is not to say that we are at war with all Muslims. But we are absolutely at war with those who believe that death in defense of the faith is the highest possible good, that cartoonists should be killed for caricaturing the prophet and that any Muslim who loses his faith should be butchered for apostasy. . .

At its most extreme, liberal denial has found expression in a growing subculture of conspiracy theorists who believe that the atrocities of 9/11 were orchestrated by our own government. . .

Such an astonishing eruption of masochistic unreason could well mark the decline of liberalism, if not the decline of Western civilization. There are books, films and conferences organized around this phantasmagoria, and they offer an unusually clear view of the debilitating dogma that lurks at the heart of liberalism: Western power is utterly malevolent, while the powerless people of the Earth can be counted on to embrace reason and tolerance, if only given sufficient economic opportunities."

I don't agree with him on everything, but what is clear is that a lot of people don't understand what we are up against. I can understand their reluctance; knowing that many impassioned, irrational people want you dead is, well, at the least disquieting. Ignoring this problem won't work, though. These issues are all too real, rather than some figment of an overly self-indulgent imagination. Don't believe me? How about this, this, this, and this? (all via Drudge) And that for reading a quote.

Do we think these or other such threats are hollow? If yes, then why are we worried about trying to stem such reactions? If no, then when are we going to unite at least in the fundamental understanding of the scope of the problem we face?

Monday, September 18, 2006

I told my parents it wasn't important

Homework is counterproductive and bad. I claim victory for all my procrastination at last. From third grade when I remember sheepishly mentioning to my mother a dinosaur report I needed to do for school (and her recoiling when I then let it slip that the multi-week assignment was due in about 12 hours), to the all-nighter I pulled to finish my last paper in grad school about managing technological change in the medical device industry. All those lost nights, grief, angst, stress, extensions, missed deadlines, etc. - all were done in a feeble attempt to worship at the feet of a false god.

Alas, if only I believed that. Instead, I know that way too much of my education, regardless of how well I eventually did, was spent in a tragic dance with a lack of personal discipline.

Just for today, though, I'm claiming vindication.

What if we needed 100,000 more troops?

There are lots of issues raised here, and touching on all of them would be a lengthy task. My style, however, with topics such as this will be to deconstruct them, focusing a single post on one aspect of the issue (with future posts to potentially hit on other parts). This isn't because the other parts aren't important, but because few people want to read chapter-length disquisitions on a blog.

In that vein, I want to look at one statement that is made at the end of this email to Rich Lowry: "You simply can't say 'we need more troops' without reinitiating the draft. That will never happen." Put aside for a moment whether or not we need more troops. If we do, can we get them short of reinstituting the draft?

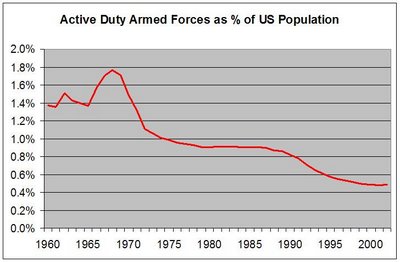

It's generally recognized that the military has slimmed down since the Cold War. I don't think, though, that the extent of this is completely appreciated. Take a look at this chart that I put together:

The figures for active duty personnel come from here (alas, only through 2002), while the population figures come from here (Table 2). What this tells us is that the "military participation rate," if you will, has dropped from ~0.9% in the 1980's to ~0.5% today. With a population nearing 300 million, each 0.01% equals almost 30,000 troops.

There are other forces at play, obviously; more detailed work would need to account for the portion of the population of appropriate age, the higher level of female participation in the military now versus in the 1980's, etc. However, the directional conclusion remains the same: a participation rate nearly twice today's was sustained throughout the 1980's without the use of a draft.

Today is, of course, different: we are at war, unemployment is lower, more people choose to go to college, etc. Yet the scale of change in the participation rate necessary to bring in, say, an additional 100,000 soldiers (and I don't hear anyone saying we need another 1 million) is so modest in a historical context, that it begs the question: what would we need to do to recruit those incremental soldiers in a non-compulsory manner?

And so here is an initial, humble suggestion: if we do decide that we need more soldiers, be they 100,000 or some other figure, let's try to recruit the very best we can and do that the same way a business might look to attract additional (qualified) employees. If we can't fill the positions as they are, then let's pay more, or make other changes which would, at the margin, change the number of people who choose to volunteer. People join the military for much more important reasons than pay or benefits, but to suggest that those things play no role in the decision of many is simply untrue. I don't know how sensitive the marginal propensity to enlist is to changes in salary, but I do know it would be easy enough (albeit potentially expensive) to find out if necessary.

We may have too few troops, we may have the wrong mix of troops, we may have troops that we are deploying poorly, and we may be having trouble finding people who meet our current criteria. All that could be true (although I don't agree with it all), but it still tells us almost nothing about whether or not we need to reinstitute a draft.

UPDATE: Welcome Instapundit readers. This blog is about 2/3 politics and 1/3 finance/economics. Feel free to check out some of the other posts if you enjoyed this one.

Sunday, September 17, 2006

Hopefully they're at least practicing

Oh, and since this blog is new, and readers are still getting to know my sense of humor, let me say that my comment above is meant as a joke. I think.

Wonder how much they could get for About.com?

"The housing boom would never have lasted as long as it did if mortgage lenders had to worry about being paid back in full. But instead of relying on borrowers to repay, most lenders quickly sell the loans, generating cash to make more mortgages." - New York Times editorialNot to point out the obvious, but don't you think that the people buying the loans, are, well, you know, interested in being paid back? And therefore would be unwilling to buy pools of mortgages that they thought would have higher than acceptable default rates. I'm just saying . . .

Closer than we think?

Then, before I get to it, I see the cover of this week's Time. Maybe I was wrong about attention being paid. Or, at least, the word is going out that this issue is likely to escalate in the near future.

For the record, I think Krauthammer is too pessimistic about the economic impact of a strike against Iran. What markets hate more than anything else is uncertainty (for reasons we'll spend lots of time on in future posts). In a perverse sense, then, the kind of military action that most recent pieces seem to suggest (air campaign of limited duration, perhaps coupled with some more defensive naval activity) would actually relieve some of that uncertainty by taking other options off the table (e.g. a near-term nuclear-armed Iran, a US ground action). Assuming, of course, that such a limited military action actually works, meaning that it at least sets back Iran's nuclear efforts for a number of years (a point on which I'm still not fully convinced it would).

Are the costs, whatever they are, worth it? Krauthammer sums it up nicely:

"Then there is the larger danger of permitting nuclear weapons to be acquired by religious fanatics seized with an eschatological belief in the imminent apocalypse and in their own divine duty to hasten the End of Days. The mullahs are infinitely more likely to use these weapons than anyone in the history of the nuclear age. Every city in the civilized world will live under the specter of instant annihilation delivered either by missile or by terrorist. This from a country that has an official Death to America Day and has declared since Ayatollah Khomeini's ascension that Israel must be wiped off the map.Although I wish the question was whether the "West" was willing to do that, unfortunately I fear the real question is whether America will be.

Against millenarian fanaticism glorying in a cult of death, deterrence is a mere wish. Is the West prepared to wager its cities with their millions of inhabitants on that feeble gamble?"

Not the most unified of tickets

"Her campaign tried to change the subject yesterday, rebroadcasting a 30-second television advertisement that stressed Ms. Pirro’s record as a former district attorney of Westchester County. . . The ad ran upstate this summer, but a Pirro aide said the campaign would now 'saturate' New York City television markets with it."

Here's the ad (click on the first video). The problem? The first three words out of Pirro's mouth are, "Like Eliot Spitzer . . ." For non-New Yorkers, Eliot Spitzer is the current Attorney General, but also the Democratic candidate for NY Governor.

Now, I suppose some would argue that Pirro mentions Spitzer since he is the sitting Attorney General, and wants to show that she has a similar background, etc. Of course, a gadfly might suggest that her invoking of his name is a desperate attempt to associate herself with the guy who's leading the Republican nominee by 46% in the above linked poll, regardless of the effect on the rest of the ticket or the party itself.

So, who bears responsibility for the situation the NY GOP finds itself in, where it looks likely to get swept in all statewide races come November? Well, here is at least a place to start.

Friday, September 15, 2006

About the name

Taking the second part first, a "gadfly" is simple enough - "a person who persistently annoys or provokes others with criticism, schemes, ideas, demands, requests, etc." Those who know me will probably agree with that description, especially if I've already had an adult beverage or two. But, to be fair, I always try to do it with a smile.

As for "grade-one," that's a reference to an essay I read when I was 13 by William Golding called "Thinking as a Hobby." He lays out what he sees as the three types of thinkers in the world: grade-three ("feeling, rather than thought"), grade-two ("the detection of contradictions"), and grade-one ("which says, 'What is truth?' and sets out to find it"). This blog is aiming for One, undoubtedly will stumble about in Two, but will have a lot of fun at the expense of those in Three.

Take them together, and what I hope to create is a gadfly with a purpose, an irritant with a goal. Point out things that don't make sense? Most definitely. Hopefully, though, at the same time we can move the collective conversation forward ever so slightly.

And, if not, I'm pretty sure "Grade-Two Gadfly" is still available.

Welcome

We're going to touch on politics, finance, economics, current events and other stuff. I say "we" because I've left the comments option on, and I hope that over time there will be some good dialogue that goes on here (what else could a gadfly hope for?). But I'm sure it will take a while to get that up and going, so for a bit I will just have to opine myself.

The approach is going to be serious, but hopefully fun. I believe in data, evidence, and analysis, and I'll do my best to use all three as the need arises. The tone will be opinionated, but above all sane and civil (and that goes for the comments, too - this is my little corner of the web, and you are warned). People who disagree are encouraged and welcome; people who can't discuss things like adults are not.

One thing that will separate this from some of my other favorite political blogs is that many of them (say here and here) are written by lawyers. I'm a finance professional, which will inform (some) of my choices of topics, as well as the approaches I take. It also means that we may do a little number crunching around here; probably nothing too crazy, but just enough to see if things other people are saying pass the "smell test." Hopefully it will make for a fresh approach; if not, no harm done.

Oh, and conspiracy theorists aren't going to like this site. Just to warn you.

Bear with me the first couple of weeks, as I work through things like playing with the format a bit, getting links up and running, finding a sustainable pacing that works, etc. As for what to expect, I think that initially there will be a bit more about politics and foreign policy given the upcoming election and ongoing war, with financial stuff lagging but eventually picking up as well (my vision is that these posts will be more original and less "linky" than the politics ones, but we'll see how it goes). And of course, there will also be a random sampling of other things that catch my interest as time goes on.

Thanks for stopping by, and don't be shy about letting me know what you think.